UToledo Astronomy Discovery Defies Model of How Stars Are Born

March 18th, 2021 by Christine BillauUsing data from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, astronomy researchers at The University of Toledo found that torrential outflows of gas from infant stars may not stop them from growing.

The research published in the Astrophysical Journal squelches commonly assumed models of star formation.

Nolan Habel, Ph.D. candidate in the UToledo Department of Physics and Astronomy

The first author of the study is UToledo graduate student Nolan Habel.

“We looked at 304 young, still-forming stars called protostars in the star-forming region of Orion — the nearest major star-forming region to Earth,” said Habel, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Physics and Astronomy. “Our results fly in the face of the most common explanation of how exactly protostars go from objects with dense envelopes of collapsing hydrogen gas to an isolated star.”

In the largest survey of protostars to date, Habel and Dr. Tom Megeath, UToledo professor of physics and astronomy, focused on one question: how much of this gaseous material ends up on the star and how much is blown away from the star in the formation process?

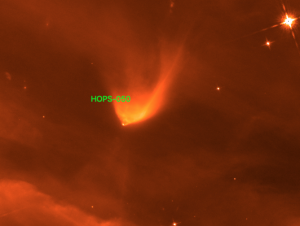

“There are remarkable ‘U’- or ‘V’- shaped structures extending to the north and south of a protostar,” Habel said. “They are actually hollowed-out cavities carved into the surrounding gas by hurricane-like winds or jets of material expelled from the poles of the protostar.”

They expected that as a protostar gets older, they would see these cavities in the surrounding gas cloud sculpted by a forming star’s outflow grow steadily, as theories propose, but they found this isn’t necessarily the case.

The study shows no evidence that the cavities were growing steadily as the protostar aged.

“In one stellar formation model, if you start out with a small cavity, as the protostar evolves, its outflow creates an ever-larger cavity until the surrounding gas is eventually blown away, leaving an isolated star,” Habel said.

An image from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope reveals the chaotic birth of stars in the Orion complex, the nearest major star-forming region to Earth. The stellar outflows are carving out cavities within the gas cloud, composed of hydrogen gas.

The study shows that gas clearing by a star’s outflow may not be as important in determining its final mass, as conventional theories suggest.

“Our observations indicate there is no progressive growth that we can find, so the cavities are not just steadily getting bigger until they push out all of the mass in the cloud. There must be some other reason why the gas doesn’t all end up in a star.”

The Hubble images reveal details of the cavities produced by protostars at various stages of evolution. The UToledo team used the images to measure the structures’ shapes and estimate the volumes of gas swept away to make the openings. From this analysis, they could estimate the amount of mass that had been cleared out by the stars’ outflows.

“We find that at the end of the protostellar phase, when most of the gas has fallen from the surrounding cloud onto the star, the young stars can still have fairly narrow cavities,” Megeath said. “There is a commonly held picture that what halts the infall of gas and determines the masses of stars are the growth of these cavities as the outflows scoop up the gas. This has been a pretty fundamental idea of how star formation proceeds, but it just doesn’t seem to fit the data here.”

In addition to Hubble, the researchers also used data from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope and the European Space Agency’s Herschel Space Telescope, both of which are no longer operational.

Future telescopes such as NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope will probe deeper into a protostar’s formation process. Webb’s spectroscopic observations will observe the inner regions of the gas envelopes surrounding protostars in infrared light, looking for outflows in the youngest sources. Webb also will help astronomers measure the accretion rate of material from the disks onto the stars, and study how the disks launch the outflows that clear the cavities.

Christine Billau is

UT's Media Relations Specialist. Contact her at 419.530.2077 or christine.billau@utoledo.edu.

Email this author | All posts by

Christine Billau